å‚åŠ äº†ä¸‰å€‹è‰ºæœ¯å®¶èˆ‰è¾¦çš„â€œä¸‰è¡Œå¯¦é©—å®¤â€å·¥ä½œåŠï¼Œæ¯ä¸€å€‹åƒèˆ‡è€…寫了一個三行詩給å¦å¤–一個ä¸ä¸€å®šèªè˜çš„人,在ç£å¸¶ä¸Šæœ—讀錄音。æ¯ä¸€å€‹äººéŒ„完之後,組織者收集了åˆæŒ‰ç…§äººåé‡æ–°ç™¼çµ¦æ¯ä¸€å€‹äººå¯«çµ¦ä»–的三行朗讀。發完組織者說“好,那我們今天就這樣çµæŸå•¦ï¼Œä½ è¦è‡ªå·±å›žå®¶å¾Œæ‰¾æ–¹æ³•æ’æ”¾ä½ çš„ç£å¸¶â€ã€‚當然家裡沒有,ä¸çŸ¥é“è¦ç‰å¤šä¹…æ‰èƒ½è½åˆ°é€™é¦–詩就拿著這個神秘的å°ç£å¸¶èµ°ã€‚

工作åŠä¹‹å¾ŒåŽ»æ‰¾æˆ‘姑å§ä¸€èµ·åƒé£¯ï¼Œå¥¹å‘Šè¨´äº†æˆ‘大伯éŽä¸–了。第二天她和其他阿伯去收拾大伯的屋,è¦æº–備把他30年一個人ä½çš„房å還給政府。他們回來之後給我一個è€è¡ŒæŽç®±ï¼Œè£¡é¢æ”¾äº†ä¸€äº›å¤§ä¼¯çš„æ±è¥¿ã€‚å…¶ä¸æœ‰ä¸€å€‹å°AIWA放音機, 外殼壞了但是還能用。è½äº†ä½ 給我寫的三行詩,è½åˆ°åœ¨é‚£ä¸‰è¡Œä¹‹é–“æˆ‘å’Œä½ ä¹‹é–“çš„è·é›¢ï¼Œä¹Ÿè¨±ä¹Ÿå°±æ˜¯é€™å€‹åœ°çƒä¸Šçš„æ¯ä¸€å€‹äººèˆ‡å¦å¤–一個人的è·é›¢ã€‚

immigrant’s on kawara

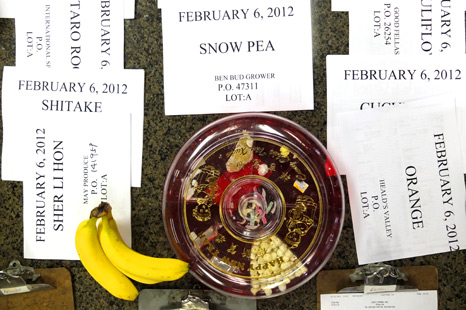

ç¥æ‚¨…这龙年åˆå五 wishing you, on the fifteenth day of a new lunar year

Posted by 丫 | reply »for rene, wendy, small O and rancière’s translator steven

The waiting room of the Department of Motor Vehicles is of course a dismal place: expectedly generic cream-coloured walls, empty except for an L.E.D. number call board and the state logo plaque, a television in the corner and a single formica counter top with ball-point pens on chains attached to it. The rows of chairs are arranged in two directions, presumably for maximum television visibility, but most people look down at mobile phones anyway, or stare into space somewhere beyond the range of the television set.

But today it is an exciting scene to return to, and waiting vacuously feels like a nostalgic act. It looks exactly the same as it did when I came here many years ago, the same bureaucratic cream wall for the same bureaucratic procedure. And for all it’s clichédness, i’ve missed the variety of colour presented behind all that blankness of expression that can only be witnessed in North America. There are probably as many planets and cultures here as there are individuals in the waiting room, but they’ve cleverly staggered the numbering system so that we don’t examine things too linearly. An Asian boy wearing a shiny black down jacket sits down next to me, his transparent document folder neatly organised with all the required paperwork. He doesn’t have to wait too long, and when his number is called I feel the surprise in the black-rimmed eyeglasses slouched on his nose as he walks away. There is a bearish old man who inches across the room with a walker, but his loud, craggy voice with a strong southern accent (enough to satisfy Michael) flirts with the DMV employee like a slick, young stud; other people in the waiting room smile with their heads down. Everyone is polite.

A skinny, stereotypically troubled looking girl (black eyeliner) wears a sleeveless short dress and lazily kicks her three bags——two black and one teal with an E.T. airbrush print on one side——on the ground in front of her as she moves up the queue. A mother and her two daughters, all dressed in black, wait seated together in the row in front of me. The girls take turns using their iPhones or handheld mirrors to check themselves in preparation for having new ID photos taken. Mother gets up at one point to remind the DMV employee to replenish the toilet paper in the women’s restroom and upon her return, says to the girls, “Well…that’s taken care of.”

Beyond a staggered numbering system of waiting, it is difficult to know whether or not we exist in the same time-space. How did you assume that there was a consensual notion of reality? When could we have used the word “us”? For all our attempts to describe it so, how do we know a relation?

My thoughts move from the backs of people’s heads through to the ninja movie on TV. Flying black-clad zombies are pierced by tips on how to save money and political campaign advertisements. There aren’t any plants here. The mini-blinds along the windows are all open to differing degrees. It’s cloudy outside.

Attention diverts to my own electronic devices now, too. I brought the silver and black mobile phone you left when you moved away. I put my SIM card in it and suddenly our lives are mingled into one interface, except that much of mine is sharpened into little rectangles of an unrecognised encoding. Bureaucracy, an organised form of protectionism, just as easily renders us illiterate as it claims efficiency. For the same reason it is not possible to delete the folder of your text messages, so these few months of your life stay stuck in my hands, another life in another city not here, amidst 60 odd foreign faces at the Department of Motor Vehicles. Everyone looks bland here, but somehow it makes certain relations all the more apparent, and I feel close to you somehow, looking inside-out. I wish you were here to pass the time with me, to run errands together and wait in line and make bureaucratic procedures intimate, like bitter jokes about getting married and having kids.

These are momentary islands of waiting for another radical shift of the senses. Waiting is like insurance for belongingness, and realising now that I’ve missed you all this time I feel a closeness that only occurs in distance. not sure whether I prefer it this way or not.

I ask the attendant behind the computer how long the wait is. “That’s the question of the day”, he quips, and of course we both know that we can never really know how long we have to wait. Ask how much work we can get done in an interim period, or ask how a simple quip and come-back rides us through the day. Ask a slippery American tongue, ask for a decade. When I asked her once about love she said she would choose the option that gave the most possibility. But even no is a possibility. So I try not to count too much.

Posted by 丫 | reply »biography Posted by 丫 | reply »

“Visibility makes bare the conflictual nature of autonomy.”

“Visibility makes bare the conflictual nature of autonomy.”

I don’t remember anymore exactly what context these words were written, random scribblings here and there, nowhere near as precise as her drawings, my notes having lost their specificity in time and space——depending upon one’s mood, everything can be about art or love or politics. The truth of that is an X-X-X, or “cha cha cha“, as she says, and even if i didn’t want to teach anybody anything, words fall out sloppily and ego still wishes for someone to pick them up.

“Visibility makes bare the conflictual nature of autonomy.”

I write it down because i don’t know who you are, or perhaps that’s merely a reflection of how little i know myself. Our togetherness isn’t really about a specificity in time and space, so there was no need to ask for visibility in the first place; we could accept speed, the vaguenesses of motion, non-places and all that sort. And why, would that invisibility make us more connected in some way, as if we could melt into some general idea, the seamlessness of an a-history? “Let’s not leave any traces,” I remember thinking, but my, now isn’t that sloppy.

Autonomy was seldom and always the question. Even in art, love, politics and science, like cha cha cha, it was actually the struggle of a singularity, call it human, but this singularity was much more a plea, a collective bargain, only yeah, maybe without singular demand. To be seen is not the same as being heard, and if we tried merely to subsist, voiceless for centuries, would that mean we were toiling backwards, trapped or free? She said today, “It would be very difficult to leave, being born into this kind of life, and if we did, it would be very difficult to come back.” I thought of the freedom of precipices, another dramatic moment, that articulation such that we are changed yet again, forever. What does it mean to be heard?

Are we co-conspirators, simply because you see me; what makes this withness, and if love is the thing to turn anyone into people, what holds us together and must we stand apart from everyone else? There are wars in politics, disagreements in science, revolutions in art. But love is both an anyone and a people, constantly exchanging identities, on a precipice. I see you…

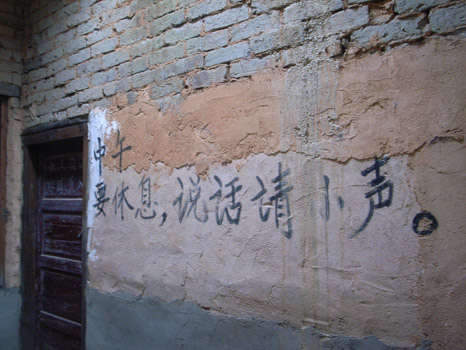

—all images taken Autumn 2011 from å¼ è°·è‹± Zhangguying, Hunan Province

—all images taken Autumn 2011 from å¼ è°·è‹± Zhangguying, Hunan Province

courtship

china is like greece. china is like isreal. china is like peru. china is like

china is not like.

展览题为“如何独处†The Title of the Show is ‘How to Be Alone’

1// 《但愿我能为您æ绘得更好》第二期里献给å‹åçš„æŒ: “èœå•ï¼é‚£ä¹ˆä»Šå¤œä½•å¤„是京都ï¼çŒ«å’ªé©¬ç³â€ï¼ˆæ¼”唱者:“声音å‘导â€ä¹é˜Ÿï¼Œå£°éŸ³ä»‹å…¥éƒ¨åˆ†ï¼šä½•é¢–é›…ã€ä½•äº¬è•´ï¼‰ From the publication iwishicoulddescribeittoyoubetter number two, for Tomoko: “Menu/So Where Is Kyoto Tonight?/Mullin The Mog” by DirectorSound with inserts by Elaine W. HO and Anouchka van DRIEL

2// “解手与生产â€ï¼Œå°è¯•ä¸ºé«˜çµå£å¤´ç¿»è¯‘Paul CHAN的文本 “Pee and Productionâ€, trying to orally translate a text by Paul CHAN to GAO Ling

3// 爸爸骑ç€æ‘©æ‰˜ï¼Œ å„¿åå在åŽåº§ä¸Šæ‰“ç€å¿«æ¿ï¼Œ 我们一起在儿童电影夜场å–了点酒,家作åŠ2010å¹´Â The boy comes home with his father playing kuaiban, we had been drinking at the kids’ movie night, HomeShop 2010

4// “ä½ å¥½å‘€ï¼ŒåŠ³ä¼¦æ–¯è€å¸ˆï¼” 这段对我外婆的采访录音是1991年我ä¸å¦åŽ†å²è¯¾ä¸Šçš„家åºä½œä¸šâ€”—“å£è¿°åŽ†å²â€ï¼Œæˆ‘妈妈也在“其间â€ã€‚ “Hellll-o Mizz Lawrence!” An oral history project, my grandmother, mother and me, 1991

5// 五å²çš„我,在数数和唱æŒÂ When I was 5 years old, counting and singing

6// 我在è´ä¹°çš„è¿·ä½ SDå¡ä¸Šæ‰¾åˆ°äº†70多首æŒï¼Œä»Žä¸é€‰äº†å首æŒå¹¶é€šè¿‡æ•°ç 处ç†ï¼ŒæŠŠå®ƒä»¬çš„节æ‹ç»Ÿä¸€æˆæ¯åˆ†é’Ÿ120æ‹ï¼ˆç‰¹æ®Šæ„Ÿè°¢Ryan KING在数ç 处ç†ï¼‰ Music found on the micro-SD cards purchased to create this work, whereby among 70 songs in total ten were chosen and digitally synced at 120 beats per minute (processing courtesy of Ryan KING)

—–

装置在《第三房:如何独处》展览,站å°ä¸å›½ï¼Œ2010å¹´11月11æ—¥ï¼2011å¹´1月24æ—¥

Installation part of The Third Party: How to Be Alone (or nowhere else am i safe from the question: why here?), on view at Platform China, 11 November 2010 – 24 January 2011

sunday

walking around a new city on a sunday morning, thinking about cakes and the lives you will never live. getting lost. it’s raining and the sloping roof of the opera house makes you miss architecture. a scone with fruits and nuts, the king riding by.

Posted by f | more »