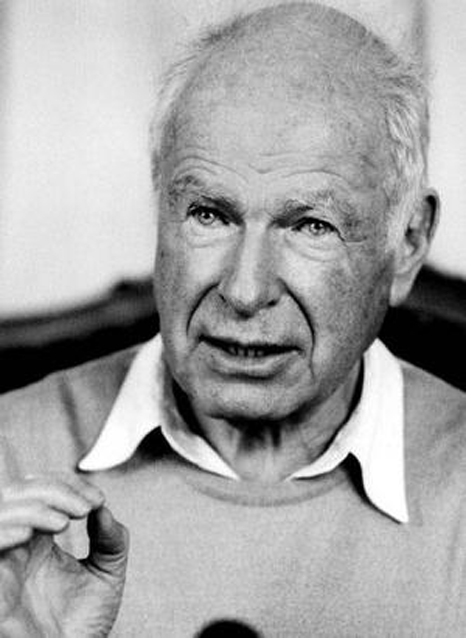

Peter Brook has been a director of the Royal Shakespeare Company and currently heads the International Centre of Theatre Research in Paris. He has directed over fifty major productions in London, Paris, New York and other places, as well as Opera and film.

Quotations from Between two Silences

Yes, this is this whole question of innocence and experience. A child up to a certain age is complete within the possibilities available at that age, but he hasn’t fulfilled all his possibilities. He then comes into an awkward period when new possibilities begin to emerge and they stop halfway. And then all the trouble begins. Physically, you can grow up to a certain age…You just grow, grow, grow, naturally, and then you’re grown up. Your body’s grown up, but that doesn’t mean that your inner possibilities are fully realized. And at that moment the innocence is lost and you go into complication, and every problem exists. What you have to do is to go through them and develop to a new innocence…One can’t say that being a child is really an aim for an adult, but at the same time being like the adult that we all are isn’t enough. That’s why so many writers have used the image of going through a forest; there’s the childhood and then there’s this going through a forest which often is very dark and tangled, and if it’s possible to get out of it, then a new form of what you can call innocence is found. One innocence is given; the other is discovered.

…

I think you can explore yourself if you’re not interested in exploring yourself, but in exploring other people and exploring your relations with other people. The first thing that can really destroy the true possibility of an actor is that he’s too interested in exploring himself. A sensitive actor can find himself, for instance in a very tough and brutal group; he may have a real ideal, his innocence may still be there, and he looks round he sees that the director is vulgar, the other actor are exhibitionists, and all that he has longed for in the theatre is being betrayed before his eyes.

…

…it seemed to me that what happens inside the picture frame had to be made as fascinating as possible. So, from the very start my biggest interest on the design. It seemed to me that the image that you say through the picture frame was the image of another world…And I found this stimulating, exciting, dynamic; I rapidly learned that the image that you are looking at couldn’t be too complete. If it was oversaturated, the imagination wouldn’t flow anymore. The image that you looked at had to suggest a real world without being completely a real world.

…

It was one of the most interesting and important subjective experiences, to see how, in the theatre, anything to do with design is inseparable from the fact that theatre is not a static image. It is not even an image in movement; it is a play in movement. It is interrelationship within something which unfolds like a great spool of film. From the beginning of the play, and at each moment, image, sound, movement, word is having its effect o n an audience, bringing the audience closer to the characters, more into certain human situations, bringing their interest up, then lowering it for a moment.

…

I think that the designer must bring a very positive contribution of his own, but he must start by recognizing and respecting that the costume, for example, is the actor’s tool, and that the actor start’s with something very, very tiny in himself. At first he’s very protective about it because it’s also a formless hunch which he’s letting grow…then gradually the actor begins to realize that he has to communicate and share what he’s doing, and what he has secretly begun to find is able to go outwards. For it to go outward, there comes a point where the costume becomes one of the biggest tools for projecting outwards to the audience.

…

But we can’t make relationships; we can let relationships, because that’s what any story, any play of any description, anything human, is about: relationships. In scratching away to find the bedrock of that, you’re doing something like a painter or sculptor who is eliminating what’s not necessary until the shape is there. That shape then becomes aesthetically pleasing, and I think that is what touches you. You see, it’s inhabiting the space, but not for “artistic” reason.

…

I think that really goes back to why Westerns are so interesting, and have always been, from the beginning of cinema. Just that shot of a horse galloping. That’s why “movies” is a very good word. Movies really mean that it’s interesting because it moves. In the theatre, you have to be moved, and that’s much more difficult.

…

…theatre as “the reflector of reality,” and that means that whatever happens in the theatre isn’t real; in the best sense of the world, it’s an imitation. That’s why we can look at it. It isn’t the real thing, but an expression of the real thing through a mirror. Anything that happens in the theatre is like a metaphor; it’s not the thing itself, but it helps you to understand the things because the real thing is not this but it’s like

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jutta Tengben

I found a great…

buy proxies

I found a great…

scrapebox proxies

I found a great…